Objective 2: Enable individuals to manage their health information and participate in their care across the cancer continuum.

A core principle of connected health is that individuals are empowered to decide when, whether, and how much to participate in their health and healthcare (see Principles of Connected Health in Part 1). Decisions about participation may change over time. Connected health tools are needed to ensure that people at risk for cancer, cancer patients, and cancer survivors have access to the information they need when they need it and in formats that meet their needs. The latter includes cultural and linguistic sensitivity. When it is appropriate and patients agree to share, information also should be accessible by family members and caregivers, who often play critically important roles in supporting people with cancer.

The Right to Obtain Health Information

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) establishes the rights of individuals and their personal representatives to receive copies of their health information from their doctors and other providers. They also have the right to have their data directly transmitted to a third party, such as a researcher. Any or all types of medical information that are used to make decisions about the individual can be requested, including summaries of office visits, diagnoses, doctors' notes, laboratory results, medication information, images (X-rays, MRIs, etc.), and account and billing information.

Sources: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Accessing your health information [Internet]. Washington (DC): ONC; [updated 2013 Jun 26; cited 2015 Nov 10]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/patients-families/accessing-your-health-information; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Individuals' right under HIPAA to access their health information 45 CFR § 164.524 [Internet]. Washington (DC): DHHS; [cited 2016 Sep 5]. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/access/

Action Item 2.1: Develop and validate interfaces and tools that support individuals’ engagement in their care across the cancer continuum.

People who are actively involved in their health and healthcare tend to have better outcomes and care experiences, improved quality of life, and, in some cases, lower costs.[1-4] For example, an analysis of patients in a large health system found that higher Patient Activation Measure scores (see Patient Activation Measure) were associated with better health outcomes for 9 of 13 indicators, including smoking status and screening for cancer. Furthermore, increases in activation scores over time were linked to improvements in health outcomes.[2]

Patient Activation Measure

The Patient Activation Measure is a metric used to quantify engagement, activation, or self-management capabilities. It assesses patients’ knowledge, skill, and confidence to manage their health and healthcare. A growing body of literature indicates that patients who are more activated as measured by the Patient Activation Measure make more effective use of health care resources and engage in more positive health behaviors compared with other patients.

Sources: Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-26. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15230939; Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23381511

Patient engagement is a central pillar of health policy and healthcare reform efforts in recent years, including the Affordable Care Act. This has been accompanied by a growing emphasis on self-management, shared decision making, and patient-centered care that is respectful of and responsive to individuals’ preferences, needs, and values.[5] Health information technologies and digital communication tools provide opportunities to enhance individuals’ active participation in their health and healthcare by linking them to information, resources, and people who can support and guide them. These tools could be particularly useful for people managing their health and navigating complex healthcare systems after a cancer diagnosis, as well as those seeking to reduce their risks for cancer.

Numerous consumer-facing, health-related tools and apps have emerged in recent years, including some related to cancer.[6-8] Many healthcare organizations have developed patient portals (see Patient Portals), and the Apple iOS and Android app stores include hundreds of health-related apps.[9,10] Such tools and apps are only the tip of the iceberg. The connected health and wellness market is projected to top $117 billion by 2020, and consumer-facing products and services—including those developed using tools such as ResearchKit and CareKit (see Apple ResearchKit and CareKit)—are expected to play a significant role in this growth.[11] While exciting, current activity is not sufficient to fully harness the potential of connected health for cancer. It is not enough to create more tools; the focus must be creating better tools that effectively support individuals’ active participation in their health and healthcare and help overcome barriers that still exist based on culture, literacy, education, comprehension, and broadband access.

Patient Portals

Many healthcare organizations have developed patient portals that enable patients’ access to some information in their health records. Some portals also permit patients to exchange secure messages with providers, schedule non-urgent appointments, request prescription refills, update contact information, make payments, download and complete forms, and/or view educational materials. Although study results have varied and opportunities for improved usability and functionality have been identified, use of patient portals has been linked to improvements in medication adherence, patient-provider communication, patient satisfaction, self-management of chronic disease, and uptake of some preventive screenings and services.

Sources: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. What is a patient portal? [Internet]. Washington (DC): ONC; [updated 2015 Nov 2; cited 2016 Feb 11]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/faqs/what-patient-portal; Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e44. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25669240; Kruse CS, Argueta DA, Lopez L, Nair A. Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e40. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25707035; Irizarry T, DeVito Dabbs A, Curran CR. Patient portals and patient engagement: a state of the science review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e148. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26104044

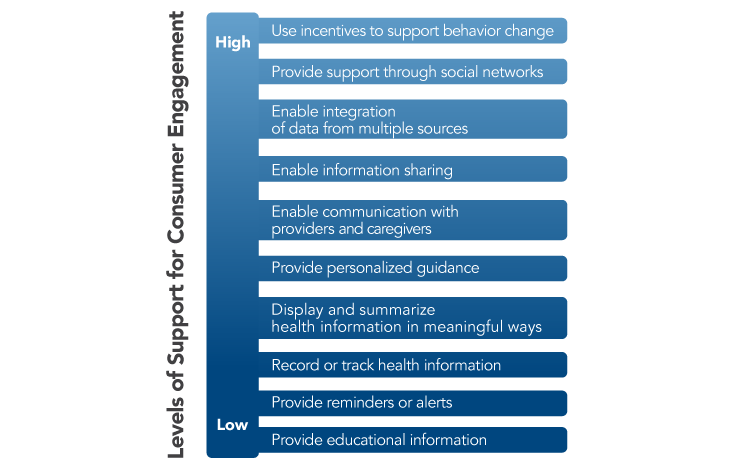

The President’s Cancer Panel urges healthcare organizations and health IT developers to develop tools and incorporate features that support high levels of user engagement. Research funding organizations should create initiatives to spur development of consumer-facing apps and tools. Such tools should reflect the wide variations among people in their preferences and needs for information and tools. The Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) Patient Engagement Playbook provides guidance for enhancing patient participation using patient portals and other health IT (see Patient Engagement Playbook). Examples of strategies to support varying levels of user engagement are shown in Figure 5. While many existing tools and apps engage users in their health and healthcare in very limited ways (e.g., providing general information about a topic or displaying raw data),[9,10] technology has created opportunities to do much more. Tools should help individuals interpret their data, displaying information in plain language and using visual aids when appropriate based on patients’ preferences. Connected health tools should incorporate decision support to help users weigh their options when faced with choices about their health and healthcare, including decisions about treatment. Tools also are needed to support patients’ communication with providers and peers and enable sharing of data with whomever they choose—other providers, caregivers, researchers, or others. Connected health tools have great potential to support behavior change and progress toward health goals (e.g., smoking cessation, physical activity), which may help reduce cancer risk or improve cancer-related outcomes. Only a small proportion of existing consumer-facing health- and cancer-related apps focus on behavior change, and very few of these have been tested for efficacy.[10,12] While there is much reason for optimism about the potential of connected health tools, there also is reason for caution about drawing conclusions before more data are available.[13] Developers, information scientists, and behavioral scientists should partner to ensure that robust evaluations are conducted. There also are opportunities to use artificial intelligence to enhance consumer-facing apps and tools.[14] Some examples of tools that support individual engagement are shown in Box 1.

Patient Engagement Playbook

The Patient Engagement Playbook is an evolving resource for providers, practice staff, hospital staff, and other innovators seeking to use health information technology to engage patients. The Playbook is a compilation of tips and best practices related to patient enrollment, features desired by patients, patient rights to access or request transmission of their health data, sharing of data among providers, caregiver proxy access, and integration of patient-generated health data.

Source: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. Patient engagement playbook [Internet]. Washington (DC): ONC; [cited 2016 Jun 16]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/playbook/pe/

Figure 5

Levels of Support for Consumer Engagement Provided by Connected Health Tools

Source: Adapted from Singh K, Drouin K, Newmark LP, et al. Developing a framework for evaluating the patient engagement, quality, and safety of mobile health applications. New York (NY): The Commonwealth Fund; 2016 Feb. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/feb/evaluating-mobile-health-apps

Box 1

Tools Supporting Consumer Engagement

-

My Journey Compass and MyPath

The Smart and Connected Health Program, a cross-agency initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation, provided funding to researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology to develop tools to support the changing needs and goals of cancer patients as they undergo treatment and transition into survivorship. As part of a pilot test of the My Journey Compass program, breast cancer patients were provided with tablet computers that included a suite of tools integrated into patients’ existing healthcare systems, as well as a broad range of clinical and nonclinical applications. Patients could customize tablets for their own personal use by downloading additional apps. The majority of patients used the tablets throughout treatment and into survivorship. Many patients reported that non-health resources—such as online games, social media applications, and YouTube—helped them cope with their cancer diagnoses and treatments. Researchers speculated that integration of health and non-health resources contributed to continued user engagement with the tablets, making it easier for patients to access health resources when necessary. The research team currently is developing a next-generation tool, MyPath, that integrates with patients’ medical records and provides customized, dynamic content based on the patient’s phase of cancer care and continuous user input.

Sources: National Science Foundation. Smart and Connected Health (SCH) [Internet]. Arlington (VA): NSF; 2016 Sep 12 [cited 2016 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2016/nsf16601/nsf16601.htm; Jacobs M, Clawson J, Mynatt E. Lessons learned from a yearlong deployment of customizable breast cancer tablet computers. Wireless Health 2015 Conference; 2015 Oct 14-16; Bethesda, MD. New York: ACM; Everyday Computing Lab. Creating interactive models of healthcare journeys to improve patient-centered care and patient engagement [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Georgia Institute of Technology; [cited 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: https://research.cc.gatech.edu/ecl/projects/creating-interactive-models-healthcare-journeys-improve-patient-centered-care-and-patient-e

-

MeTree

MeTree is a web-based family and personal health history collection and clinical decision support tool. Users provide information on medical conditions, diet, exercise, smoking, vital signs, and laboratory data, in addition to family health history. These data are used to create a 3-generation pedigree, calculate various health-risk scores, and assess risk for 20 cancers, 14 hereditary cancer and cardiovascular syndromes, and 21 other conditions. Reports are generated for both individuals and providers. Implementation of MeTree currently is being studied in an ongoing NIH-funded trial to understand how to best implement IT tools like MeTree in various settings and with diverse populations.

Source: Time to focus on your family health history. Duke Today [Internet]. 2015 Dec 15 [cited 2016 Sep 8]. Available from: https://today.duke.edu/2015/12/metree

-

PatientsLikeMe

PatientsLikeMe is a web-based community of over 400,000 patients, including many who have been diagnosed with cancer. The website enables patients to connect with other people dealing with the same health issue, providing a forum for information exchange and social support. PatientsLikeMe also provides tools for tracking and sharing symptoms, treatment information, and health outcomes. Patients can use these tools to help them manage their health, and PatientsLikeMe also aggregates and organizes the data to reveal new insights. The PatientsLikeMe Research Forum allows patients to submit ideas for research, and patients may be invited to participate in internal research projects or in projects being conducted in collaboration with outside partners.

Source: PatientsLikeMe. Home page [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): PatientsLikeMe; [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.patientslikeme.com/

My Journey Compass and MyPath

The Smart and Connected Health Program, a cross-agency initiative of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation, provided funding to researchers at Georgia Institute of Technology to develop tools to support the changing needs and goals of cancer patients as they undergo treatment and transition into survivorship. As part of a pilot test of the My Journey Compass program, breast cancer patients were provided with tablet computers that included a suite of tools integrated into patients’ existing healthcare systems, as well as a broad range of clinical and nonclinical applications. Patients could customize tablets for their own personal use by downloading additional apps. The majority of patients used the tablets throughout treatment and into survivorship. Many patients reported that non-health resources—such as online games, social media applications, and YouTube—helped them cope with their cancer diagnoses and treatments. Researchers speculated that integration of health and non-health resources contributed to continued user engagement with the tablets, making it easier for patients to access health resources when necessary. The research team currently is developing a next-generation tool, MyPath, that integrates with patients’ medical records and provides customized, dynamic content based on the patient’s phase of cancer care and continuous user input.

Sources: National Science Foundation. Smart and Connected Health (SCH) [Internet]. Arlington (VA): NSF; 2016 Sep 12 [cited 2016 Sep 14]. Available from: https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2016/nsf16601/nsf16601.htm; Jacobs M, Clawson J, Mynatt E. Lessons learned from a yearlong deployment of customizable breast cancer tablet computers. Wireless Health 2015 Conference; 2015 Oct 14-16; Bethesda, MD. New York: ACM; Everyday Computing Lab. Creating interactive models of healthcare journeys to improve patient-centered care and patient engagement [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Georgia Institute of Technology; [cited 2016 Aug 30]. Available from: https://research.cc.gatech.edu/ecl/projects/creating-interactive-models-healthcare-journeys-improve-patient-centered-care-and-patient-e

MeTree

MeTree is a web-based family and personal health history collection and clinical decision support tool. Users provide information on medical conditions, diet, exercise, smoking, vital signs, and laboratory data, in addition to family health history. These data are used to create a 3-generation pedigree, calculate various health-risk scores, and assess risk for 20 cancers, 14 hereditary cancer and cardiovascular syndromes, and 21 other conditions. Reports are generated for both individuals and providers. Implementation of MeTree currently is being studied in an ongoing NIH-funded trial to understand how to best implement IT tools like MeTree in various settings and with diverse populations.

Source: Time to focus on your family health history. Duke Today [Internet]. 2015 Dec 15 [cited 2016 Sep 8]. Available from: https://today.duke.edu/2015/12/metree

PatientsLikeMe

PatientsLikeMe is a web-based community of over 400,000 patients, including many who have been diagnosed with cancer. The website enables patients to connect with other people dealing with the same health issue, providing a forum for information exchange and social support. PatientsLikeMe also provides tools for tracking and sharing symptoms, treatment information, and health outcomes. Patients can use these tools to help them manage their health, and PatientsLikeMe also aggregates and organizes the data to reveal new insights. The PatientsLikeMe Research Forum allows patients to submit ideas for research, and patients may be invited to participate in internal research projects or in projects being conducted in collaboration with outside partners.

Source: PatientsLikeMe. Home page [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): PatientsLikeMe; [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.patientslikeme.com/

Apple ResearchKit and CareKit

Apple, Inc., has created two open-source frameworks—ResearchKit and CareKit—that enable creation of apps that connect patients to healthcare providers and researchers.

ResearchKit allows researchers to work with developers to build apps for research. This framework contains three customizable modules:

- Informed Consent enables researchers to specify study requirements and participation risks, as well as collect participants’ signatures using touch-screen technology.

- Surveys contains pre-built question and answer templates for qualitative and quantitative data.

- Active Task allows participants to collect data under partially controlled conditions using iPhone sensors such as accelerometer, gyroscope, microphone, and others.

Researchers can add custom modules, remind participants to complete surveys/tasks, and display individual participants’ data, providing an immediate benefit to study participation. In addition, participants could be recruited world-wide rather than from the immediate vicinity of a hospital or clinic. The ResearchKit app Share the Journey is highlighted in the Using Person-Generated Data in Cancer Research sidebar in Objective 5.

CareKit enables healthcare providers to create apps to help patients manage their medical conditions. CareKit includes four customizable modules:

- Care Card displays a customized care plan and tasks necessary to perform during treatment such as taking medications, changing wound dressings, or exercising.

- Symptom and Measurement Tracker monitors subjective symptoms such as pain as well as objective measurements such as temperature and blood pressure.

- Insights displays individual results to visualize trends in treatment and symptoms and make personal health inferences.

- Connect engages healthcare teams and family members as partners in the personal health journey.

Data can be stored locally in the Care Plan Store or exported using Document Exporter to be shared with anyone on the care team.

These tools can be used separately or in combination. In addition, any Bluetooth sensors could be leveraged to seamlessly collect data with participants’ permission to create powerful data collection and treatment follow-up tools.

Sources: Apple, Inc. ResearchKit and CareKit [Internet]. Cupertino (CA): Apple; [cited 2016 Aug 3]. Available from: http://www.apple.com/researchkit/; ResearchKit. Home page [Internet]. Cupertino (CA): Apple; [cited 2016 Aug 3]. Available from: http://researchkit.org/; CareKit. Home page [Internet]. Cupertino (CA): Apple; [cited 2016 Aug 3]. Available from: http://carekit.org/

Connected health tools also should enable individuals to integrate information in their health records with information from other sources. Unfortunately, the vast majority of currently available health apps are disconnected from the healthcare delivery system.[15] Adoption by health IT vendors of a limited number of standard, open application programming interfaces (APIs) would permit third-party app developers to request and use data from EHRs with patients’ permission (see Action Item 1.3 ). This would facilitate creation of a virtually limitless collection of apps tailored to the diverse needs of individuals across the cancer continuum. Among other things, API-based apps could integrate personal health data from multiple EHR systems, enabling patients to store and view all of their health information in one place. Consumer-controlled aggregation of health data is the focus of the recent ONC Consumer Health Data Aggregator Challenge.[16] APIs also create opportunities to develop consumer apps capable of sending patient-generated data to EHRs (see Part 3 ).

Developers should take note of the extensive knowledge base on patient engagement and use validated instruments to evaluate the effects of their tools on patient activation[17,18] as well as on health outcomes. Every person is unique, and a diverse suite of tools is needed to support patients’ needs and preferences. Differences in literacy and health literacy, as well as language and cultural preferences, also must be considered.[19] Regardless of the features or target population, all connected health tools—including patient portals, apps, and other types of tools—should be developed with meaningful input from intended users and have usable interfaces developed through early and iterative testing.[20] Whenever possible, interfaces should be configured for mobile devices to reflect the growing adoption of mobile devices among Americans (see Figure 1 in Part 1) and the fact that nearly one in five adults in the United States largely rely on mobile phones to access the Internet.[21] Tools also should be tested using a variety of Internet browsers. For apps and tools that collect data for research, user-friendly informed consent processes should be incorporated as appropriate.[22,23] Any tool or app that collects or stores personal health data, including EHRs, must conform to any applicable federal, state, and organizational requirements regarding privacy and security. As was discussed in a recent report from ONC, health data collected by many personal devices and web-based resources are not covered by HIPAA.[24] Nonetheless, developers should take steps to ensure that users’ health data are safe and secure. Users also must be informed of policies related to information access and sharing. This should be done in ways that are user-sensitive, not in multi-page disclosure statements that are read by few people. The Panel also is concerned about the trend toward privatization and monetization of personal health data.[25]

Individuals can, and should, choose apps that are right for them. Consumers may benefit from guidance in selecting from among the numerous connected health apps and tools that are and will become available.[15] Developers should cite credible information sources or sources of substantiating evidence for the efficacy of their products when available. Professional societies, provider organizations, and other trusted organizations may consider identifying high-quality tools relevant to their areas of focus.[26]

Action Item 2.2: Organizations should develop processes that enable individuals to flag perceived errors in their medical records and ensure that responses are provided and appropriate changes are made in a timely manner.

The President’s Cancer Panel heard from cancer patients and advocates who are frustrated about what they regard as mistakes in their health records.[27] Analyses of medical records, including EHRs, have confirmed that deficiencies in data completeness and accuracy are far too common.[28,29] Studies at two cancer centers found that the medication lists in the EHRs of more than 80 percent of patients had at least one error or omission.[30,31] Whether in paper or electronic form, medical record errors undermine patient safety and high-quality care, creating potential for dangerous drug interactions, inaccurate or missed diagnoses, and inappropriate or inadequate treatments. They also undermine healthcare professionals’ credibility, impair patient-physician relationships, and diminish the utility of health data for quality measurement, surveillance, and research.

Studies at two cancer centers found that the medication lists in the EHRs of more than 80 percent of patients had at least one error or omission.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act provides individuals with the right to request an amendment to information in their health records and requires healthcare organizations to respond to these requests within 60 days (45 CFR 164.526).[32] As connected health tools increase individuals’ access to their health information, questions about the accuracy of that information likely will become more common. However, processes for receiving and responding to change requests have not yet been incorporated into healthcare to the extent that they have been in some other industries (e.g., credit bureaus, online commerce).[33] An ONC-funded environmental scan of patient portals found that only a few encouraged or facilitated patient requests for corrections. In most cases, feedback was limited to certain types of data (e.g., allergies), and processes for addressing patient requests varied greatly.[34] Reports from patients in the literature[35] and provided directly to the Panel[27] suggest that these processes often are inefficient and ineffective.

The President’s Cancer Panel recognizes that individuals can play a key role in ensuring the accuracy of their health information. Survey results indicate that patients are eager to fill this role,[35] and involving patients in this way also may help build trust. The Panel strongly urges healthcare organizations and health IT developers to develop processes that enable patients and their caregivers to flag and request amendments to perceived errors in their medical records, preferably using connected health tools (e.g., patient portals). Providers should encourage patients to review and provide feedback on their data. Organizations should establish processes for triaging and reviewing patient concerns and ensuring that appropriate changes are made in a timely manner. Patients should receive clear messages about expected response times and be informed of the results of the review process. The Panel also notes that improvements in EHR usability and data entry practices would help reduce the number of errors in medical records and should be pursued (see Objective 3 ). There also should be clear processes for flagging and correction of errors by healthcare delivery team members.

Action Item 2.3: Create tools and services that help individuals identify cancer-related clinical trials appropriate for their particular situations.

Clinical trials are essential for advancing knowledge about cancer and its risk factors and for developing better treatments for cancer. However, low patient participation remains one of the biggest obstacles to their success. Although recent data are lacking, it is roughly estimated that less than 5 percent of adult cancer patients in the United States currently participate in clinical trials.[36,37] People not participating in clinical trials say the main reasons for nonparticipation are that they are unaware that participation is an option and they have difficulty determining whether they are eligible to participate. Moreover, one of the main factors associated with clinical trial participation is a provider’s referral, which all too often is not provided.[38,39] When surveyed, many patients say they would be willing to participate in a clinical trial if presented the option.[40] A clear role has emerged for online tools in helping to increase awareness about cancer clinical trials, particularly in the realm of social media, which has potential to spread information quickly and widely and mobilize entire communities into action. Indeed, many nonprofit and patient advocacy organizations and biopharmaceutical companies already have mobilized their constituents to participate in clinical trials via online social networks such as Twitter and Facebook.[41,42] Strategies to help participants identify clinical trials include enhancing the usability and effectiveness of current clinical trial search tools and developing new easy-to-use tools.

Various clinical trial search tools exist that are intended to help patients and physicians connect with appropriate trials. The National Institutes of Health maintains a large database of publicly and privately supported clinical trials, including cancer trials (www.clinicaltrials.gov). The National Cancer Institute (NCI) also hosts a searchable database of cancer clinical trials it sponsors (https://trials.cancer.gov). However, the task of identifying appropriate clinical trials using these online tools is daunting for both providers and patients due to the large amount of data on thousands of clinical trials housed on these sites, often including closed trials or other outdated information, and search interfaces that are difficult to use. As a result, finding suitable clinical trials requires a large amount of motivation on the part of patients and physicians, and must often be undertaken at a time when patients have competing concerns. Further, matching an eligible patient to specified clinical trial criteria often requires access to the patient’s disease profile (such as diagnosis, type and stage of tumor, or type of treatment). Obtaining this level of disease-related information creates additional burdens for patients.

Next-generation resources that provide individuals with useful clinical trials information and facilitate the clinical trial matching process could have a transformational role in connecting patients to clinical trials (see Next-Generation Online Resources for Clinical Trial Matching). In coordination with the Cancer Moonshot and the Precision Medicine Initiative, NCI is partnering with the White House Presidential Innovation Fellows to create more accessible and usable formats for clinical trial data from cancer.gov. Notably, as of September 2016, these data have been made available through an API (https://clinicaltrialsapi.cancer.gov) (see Action Item 1.3 ), which provides opportunities for developing new third-party applications customized to the needs and preferences of various patient groups, advocacy organizations, and healthcare systems. One future goal of these tools could be to facilitate automated clinical trial matching wherein patient-created profiles or existing medical records (also made available through an API) are used to match individuals to clinical trials based on their specific disease profiles and preferences. These tools could be used by motivated patients, but also in clinical settings as a way to facilitate the provider’s role in the patient referral and enrollment process. For example, providers could receive alerts through their EHRs when their patients are potentially eligible for one or more trials (see Syapse Oncology in Action Item 3.3 ). While the full implementation of this vision may take time to achieve, the Panel believes it is worthy of pursuit.

The President’s Cancer Panel has identified the tremendous potential of connected health to expand individuals’ access to clinical trials. Cancer-focused organizations, research institutions, and government agencies could play a pivotal role in increasing clinical trial awareness through social media platforms and other online community resources. The Panel applauds and supports efforts to enhance access to information on NCI-sponsored trials. The National Institutes of Health should explore options for making clinicaltrials.gov information more accessible. In addition, efforts should be made to ensure that clinical trial information available through these databases is accurate and current. In particular, having well-structured eligibility and biomarker data would simplify matching of patients to appropriate clinical trials. The Panel also encourages third-party innovators to develop digital platforms such as apps that help individuals more efficiently access information in clinical trial databases. When possible, health IT developers and healthcare organizations should create automated matching tools that allow potential trials to be identified without special effort by patients or providers. The Panel recognizes that these goals are not easily attainable; however, these are areas in which innovation and entrepreneurship should be encouraged and incentivized.

Next-Generation Online Resources for Clinical Trial Matching

Many organizations already host clinical trial search tools that allow information about the patient’s specific disease profile (such as diagnosis, type and stage of tumor, or type of treatment) to be used to better match a patient to an appropriate trial.

The Cure Forward Clinical Trial Exchange is a matching service that connects patients with trial recruiters based on information the patient provides. Rather than searching for trials themselves, patients create personal profiles. Trial recruiters then can review patients’ molecular testing, clinical criteria, and location preferences and contact those who may be eligible for a given trial.

Smart Patients recently launched a new resource for colorectal cancer patients where patients can specify a few key characteristics about their situations, including the molecular profile of their tumors, to identify clinical trial participation opportunities through data that have been made available on cancer.gov. A similar tool for kidney cancer patients currently is being developed.

Sources: Cure Forward. Home page [Internet]. Boston (MA): Cure Forward; [cited 2016 Jul 11]. Available from: https://www.cureforward.com/; Smart Patients. Home page [Internet]. Smart Patients; [cited 2016 Feb 29]. Available from: https://www.smartpatients.com

References

- North Carolina Institute of Medicine Task Force on Patient and Family Engagement. Patient and family engagement: a partnership for culture change. Morrisville (NC): NCIOM; 2015 Jul. Available from: http://www.nciom.org/publications/?patient-and-family-engagement

- Greene J, Hibbard JH, Sacks R, Overton V, Parrotta CD. When patient activation levels change, health outcomes and costs change, too. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34(3):431-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25732493

- Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L, McGinnis JM, editors. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2012. Available from: http://nap.edu/13444

- Hibbard JH, Greene J. What the evidence shows about patient activation: better health outcomes and care experiences; fewer data on costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(2):207-14. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23381511

- James J. Health policy brief: patient engagement. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013 Feb 14. Available from: http://www.healthaffairs.org/healthpolicybriefs/brief.php?brief_id=86

- American Society of Clinical Oncology. Mobile applications [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): ASCO; [cited 2016 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.cancer.net/navigating-cancer-care/managing-your-care/mobile-applications

- National Cancer Institute. NCI mobile apps [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): NCI; [cited 2016 Jul 21]. Available from: http://www.cancer.gov/multimedia/apps

- The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. 41 apps to help prevent cancer [Internet]. Houston (TX): MD Anderson Cancer Center; 2014 Feb [cited 2016 Jul 21]. Available from: https://www.mdanderson.org/publications/focused-on-health/february-2014/cancer-prevention-apps.html

- Singh K, Drouin K, Newmark LP, Rozenblum R, Lee J, Landman A, et al. Developing a framework for evaluating the patient engagement, quality, and safety of mobile health applications. New York (NY): The Commonwealth Fund; 2016 Feb. Available from: http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2016/feb/evaluating-mobile-health-apps

- Bender JL, Yue RY, To MJ, Deacken L, Jadad AR. A lot of action, but not in the right direction: systematic review and content analysis of smartphone applications for the prevention, detection, and management of cancer. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(12):e287. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24366061

- ACT: The App Association. State of the app economy, 4th edition. Washington (DC): ACT; 2016 Jan. Available from: http://actonline.org/2016/01/04/act-the-app-association-releases-latest-app-industry-report/

- Payne HE, Lister C, West JH, Bernhardt JM. Behavioral functionality of mobile apps in health interventions: a systematic review of the literature. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2015;3(1):e20. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25803705

- Jakicic J, Davis K, Rogers R, King W, Marcus M, Helsel D, et al. Effect of wearable technology combined with a lifestyle intervention on long-term weight loss: the IDEA randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(11):1161-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27654602

- Piette JD, Krein SL, Striplin D, Marinec N, Kerns RD, Farris KB, et al. Patient-centered pain care using artificial intelligence and mobile health tools: protocol for a randomized study funded by the US Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research and Development Program. JMIR Res Protoc. 2016;5(2):e53. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27056770

- Mandl K, Mandel J, Kohane I. Driving innovation in health systems through an apps-based information economy. Cell Systems. 2015;1(1):8-13. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26339683

- Challenge.gov. Consumer Health Data Aggregator Challenge [Internet]. Washington (DC): U.S. General Services Administration; [cited 2016 Aug 25]. Available from: https://www.challenge.gov/challenge/consumer-health-data-aggregator-challenge/

- Graffigna G, Barello S, Bonanomi A, Lozza E. Measuring patient engagement: development and psychometric properties of the Patient Health Engagement (PHE) Scale. Front Psychol. 2015;6:274. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25870566

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, Tusler M. Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 1):1918-30. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16336556

- Sarkar U, Gourley GI, Lyles CR, Tieu L, Clarity C, Newmark L, et al. Usability of commercially available mobile applications for diverse patients. J Gen Intern Med. [Epub 2016 Jul 14]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27418347

- Rudin RS, Bates DW, MacRae C. Accelerating innovation in health IT. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):815-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27579633

- Smith A. U.S. smartphone use in 2015. Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2015 Apr 1. Available from: http://www.pewinternet.org/2015/04/01/us-smartphone-use-in-2015/

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. eConsent Toolkit [Internet]. Washington (DC): ONC; [updated 2014 Oct 31; cited 2016 Sep 11]. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/providers-professionals/econsent-toolkit

- Doerr M, Suver C, Wilbanks J. Developing a transparent, participant-navigated electronic informed consent for mobile-mediated research. Rochester (NY): Social Science Research Network; 2016 Apr 22. Available from: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2769129

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Office for Civil Rights, Federal Trade Commission. Examining oversight of the privacy and security of health data collected by entities not regulated by HIPAA. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2016 Jul 19. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/sites/default/files/non-covered_entities_report_june_17_2016.pdf

- Wilbanks JT, Topol EJ. Stop the privatization of health data. Nature. 2016;535(7612):345-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27443724

- Health IT Joint Committee Collaboration. Application Programming Interface (API) Task Force recommendations. Washington (DC): Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology; 2016 Jul 8. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/facas/sites/faca/files/API%20TF_Recommendations_Final%2007-08-2016.pdf

- President's Cancer Panel. Meeting summary. The connected cancer patient: vision for the future and recommendations for action; 2015 Jul 9; Chicago, IL. Bethesda (MD): President's Cancer Panel. Available from: http://deainfo.nci.nih.gov/advisory/pcp/pcp0715/summary.pdf

- Chan KS, Fowles JB, Weiner JP. Review: electronic health records and the reliability and validity of quality measures: a review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(5):503-27. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20150441

- Callen J, McIntosh J, Li J. Accuracy of medication documentation in hospital discharge summaries: a retrospective analysis of medication transcription errors in manual and electronic discharge summaries. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(1):58-64. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19800840

- Weingart SN, Cleary A, Seger A, Eng TK, Saadeh M, Gross A, et al. Medication reconciliation in ambulatory oncology. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(12):750-7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18200900

- Ashjian E, Salamin LB, Eschenburg K, Kraft S, Mackler E. Evaluation of outpatient medication reconciliation involving student pharmacists at a comprehensive cancer center. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2015;55(5):540-5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26359964

- Legal Information Institute. 45 CFR 164.526: Amendment of protected health information [Internet]. Ithaca (NY): Cornell University Law School; [cited 2016 Oct 25]. Available from:https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/45/164.526

- Siminerio E, Daniel JG. Patients play a vital role in improving the quality of information in their medical records. Health IT Buzz [Internet]. 2014 Jun 24 [cited 2015 Nov 11]. Available from: http://www.healthit.gov/buzz-blog/consumer/blue-button-helps-patients-improve-care-quality/

- Dullabh P, Sondheimer N, Katsh E, Young J-E, Washington M, Stromberg S. Demonstrating the effectiveness of patient feedback in improving the accuracy of medical records. Chicago (IL): National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago; 2014 Jun. Available from: https://www.healthit.gov/policy-researchers-implementers/demonstrating-effectiveness-patient-feedback-improving-accuracy

- Dullabh PM, Sondheimer NK, Katsh E, Evans MA. How patients can improve the accuracy of their medical records. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2014;2(3):1080. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25848614

- Lowy DR, Collins FS. Aiming high—changing the trajectory for cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(20):1901-4. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27043262

- Institute of Medicine. Transforming clinical research in the United States: challenges and opportunities: workshop summary. English RA, Lebovitz Y, Giffin RB, rapporteurs. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2010. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/12900

- Comis RL, Miller JD, Colaizzi DD, Kimmel LG. Physician-related factors involved in patient decisions to enroll onto cancer clinical trials. J Oncol Pract. 2009;5(2):50-6. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20856718

- Baer AR, Michaels M, Good MJ, Schapira L. Engaging referring physicians in the clinical trial process. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(1):e8-10. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22548019

- National Institutes of Health. The need for awareness of clinical research [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): NIH; [updated 2016 Mar 16; cited 2016 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.nih.gov/health-information/nih-clinical-research-trials-you/need-awareness-clinical-research

- Army of Women. Home page [Internet]. Encino (CA): Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation; [cited 2016 Aug 12]. Available from: https://www.armyofwomen.org/

- Sedrak MS, Cohen RB, Merchant RM, Schapira MM. Cancer communication in the social media age. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(6):822-3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26940041