Recommendation 4. Stimulate and maintain competition in the generic and biosimilar cancer drug markets.

The United States incentivizes innovation, in part by granting patents (property rights granted by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) and a number of exclusivities (delays and prohibitions on U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approval of competitor drugs) to manufacturers of new drugs and biologics. These protections limit competition and increase potential for profit. Once relevant patents have expired (or been successfully challenged) and exclusivity ends, therapeutically equivalent generic drugs and biosimilars can be approved, creating potential for competition and possibly driving down prices. The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 established the current approval processes for generics and provided incentives for both brand-name and generic drug manufacturers. Since that time, the U.S. generic drug market has expanded dramatically—generic drugs accounted for 89 percent of retail prescriptions in 2016 compared with 19 percent in 1984.1,2

Use of generic oncology drugs saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $10 billion in 2016.

Generic drug prices are not a driver of the drug cost problem in the United States—while the average price for the most commonly used brand-name drugs has increased dramatically in recent years, prices of generic drugs have fallen by more than 70 percent since 2008.3 The U.S. generic drug market saved the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $253 billion overall in 2016, including $10 billion in savings for oncology drugs.1 Patients share in these savings as out-of-pocket costs are substantially lower for generics compared with brand-name drugs.4 Use of low-cost generic drugs improves patient adherence to essential medication regimens and promotes better patient outcomes.5 Unlike prices for brand-name drugs, which often are higher in the U.S. than in other countries,6 prices for most generic drugs are lower in the United States than in Canada and Europe.7,8

Consumers benefit most when generic drugs enter the market in a timely manner and there is healthy competition within the generic market to ensure low prices. In most cases, the first generic competitor is priced only slightly lower than its brand-name counterpart, but prices fall more—and are less likely to increase over time—when additional generics enter the market (see Imatinib: Case Study of a Generic Cancer Drug).9,10 One study found that introduction of a second generic option reduced the average generic price to nearly half the price of the brand-name drug.9 Insufficient competition may lead to higher prices, price spikes, and/or drug shortages, which have significant consequences for patients.10-12 Efforts must be made to facilitate timely and efficient market entry of generic and biosimilar drugs for cancer to bolster competition and ensure affordable access for patients.

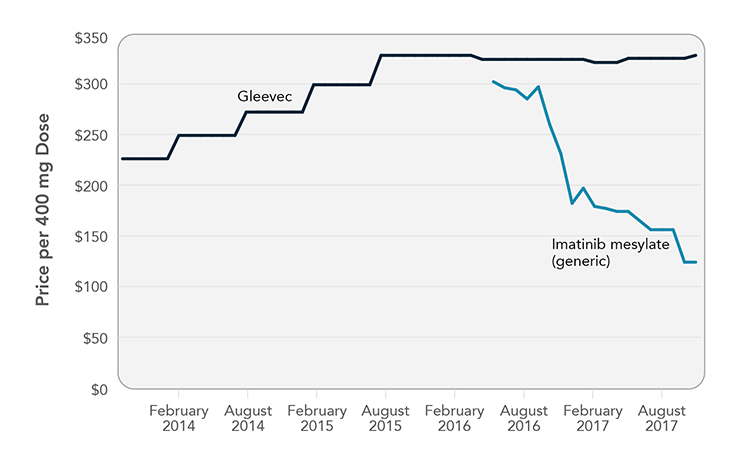

Imatinib: Case Study of a Generic Cancer Drug

Imatinib mesylate—brand name Gleevec—transformed treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, restoring normal life expectancy for many patients who previously would have lived only a few years. Gleevec was priced at $26,000/year when it launched in 2001 and climbed to $146,000/year over the next 15 years. Although Gleevec’s compound patent expired in July 2015, an agreement between the brand-name and generic manufacturers pushed back release of the first generic imatinib until February 2016. When the first generic was released, it was priced only slightly lower than Gleevec ($302 versus $324 per 400 mg tablet [National Average Drug Acquisition Cost]). Two additional generic versions of imatinib were released in August 2016, which put additional downward pressure on generic prices. The least costly option was $124 per tablet in November 2017, about $45,000 for a year of treatment. This is far less than Gleevec, but some patients still may need to pay hundreds of dollars every month for the drug.

Note: Graph shows National Average Drug Acquisition Cost, August 2013 to November 2017. Sources: Kantarjian H. The arrival of generic imatinib into the U.S. market: an educational event. The ASCO Post [Internet]. 2016 May 25 [cited 2017 Jun 23]. Available from: http://www.ascopost.com/issues/may-25-2016/the-arrival-of-generic-imatinib-into-the-us-market-an-educational-event; Langreth R. Popular cancer pill goes generic, yet patients' costs stay high. Bloomberg [Internet]. 2017 Jun 30. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-06-30/popular-cancer-pill-goes-generic-yet-patients-costs-stay-high; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. NADAC (National Average Drug Acquisition Cost) [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; [cited 2017 Dec 22]. Available from: https://data.medicaid.gov/Drug-Pricing-and-Payment/NADAC-National-Average-Drug-Acquisition-Cost-/a4y5-998d/data

FDA Should Reduce Barriers to Market Entry for Generic Drugs and Biosimilars

FDA review and approval processes should facilitate timely market entry of generic drugs. Passage of the Hatch-Waxman Act spurred the submission of thousands of generic drug applications, which required review resources that exceeded FDA’s funding for its Office of Generic Drugs, resulting in historically slow review processes.13,14 The Generic Drug User Fee Amendments, enacted in 2012, provided additional resources for FDA to review the significantly increased number of generic drug applications and established targets for review of generic applications. Since that time, FDA has made progress on backlogged generic drug applications, achieved its target review times, and approved record high levels of generic drug applications.13,14 FDA must continue to receive the resources it needs to review generic and biosimilar drug applications (Recommendation 5).

FDA also should reduce barriers for generic manufacturers to enter markets with no generic options or too few generic options to create competition. The recently launched Drug Competition Action Plan is a step in the right direction.15 The Plan will further streamline the generic application review process and outlines several strategies for increasing competition in the generics market, including publication of a list of off-patent, off-exclusivity drugs without approved generics and expedited review of generic drug applications until there are three approved generics for a given drug product. The Plan also includes support for the development and approval of “complex” generic products. These are drugs—including some cancer treatments—having at least one feature that makes them harder to “genericize” under standard scientific and regulatory pathways.16

Regulators and Policy Makers Should Promote Healthy Competition in the Generic Drug Market

Several factors influence competition in the U.S. drug market. Generic drug makers decide whether to produce a drug based on potential for profit, which fluctuates based on factors such as supply and demand, manufacturing costs, availability of competitor products, and opportunities to shift their portfolios to more-profitable drugs.

The generic drug market has provided patients with affordable access to many drugs. In some cases, however, market forces or anticompetitive behaviors limit competition, which can lead to higher prices and/or drug shortages. For example, recent analyses suggest that generic competition for some cancer drugs may be suboptimal.17,18 This may be due, in part, to smaller patient populations, which limit profit potential. Increasing consolidation of generic manufacturers also may diminish competition.19 Reports also indicate that both brand-name and generic manufacturers use a variety of strategies to prevent or delay appropriate competition, costing consumers billions of dollars each year (see Strategies Used to Delay or Limit Generic Drug Competition).

Drug shortages, price spikes, and concerns about anticompetitive behaviors in the generic drug market have prompted investigation by Congress, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and other federal agencies in recent years.12,13,20 U.S. regulatory agencies and policy makers should continue to monitor and evaluate the generic drug market to identify factors that prevent healthy competition. Deliberate efforts to limit competition must be addressed. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) should continue to consider the impact of mergers and acquisitions on competition. FTC and the U.S. Department of Justice should continue investigating potential anticompetitive behavior by brand-name and generic drug companies—including pay-for-delay settlements and price fixing—and ensure that offenders are held responsible. FDA also should continue to examine ways in which it can help curb practices—such as inappropriate use of citizen petitions and limiting distribution of drug samples for bioequivalence testing—that reduce competition.

Strategies Used to Delay or Limit Generic Drug Competition

Pay-for-delay (reverse settlement payments): Manufacturers of brand-name drugs pay or provide other compensation (e.g., agree not to market an authorized generic) to generic drug companies to delay introduction of competitor generics. This costs U.S. consumers and taxpayers an estimated $3.5 billion per year.

Citizen petitions: Individuals and/or organizations can ask FDA to delay action on a pending generic drug application. The process is intended to identify legitimate scientific and regulatory concerns about a drug, but the process often is exploited by brand-name drug companies attempting to delay competition.

Limiting distribution of drug samples for bioequivalence testing: To obtain approval for a generic drug, companies must demonstrate that their products are bioequivalent to the brand-name drugs. Often, this requires that a generic drug developer purchase physical samples of the brand-name reference drug. As of July 2017, FDA had received more than 150 inquiries from generic drug companies that were unable to access samples for testing.

Patent “evergreening” (product hopping): Some companies reformulate their brand-name drugs and encourage physicians to prescribe the new formulation. In some cases, the older drug may even be removed from the market. In addition, the new formulation may itself be protected from competition by patents and/or exclusivities. In addition, as a result of these activities, generic substitution of the original formulation may be made more difficult or impossible.

Price fixing: Generic drug manufacturers agree to a certain price or price range—usually higher than market forces would allow—for their respective competing generic drugs.

Sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. ASPE Issue Brief: Understanding recent trends in generic drug prices. Washington (DC): ASPE; 2016 Jan 27. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/175071/GenericsDrugpaperr.pdf; Federal Trade Commission. Authorized generic drugs: short-term effects and long-term impact: a report of the Federal Trade Commission. Washington (DC): FTC; 2011 Aug. Available from: https://www.ftc.gov/reports/authorized-generic-drugs-short-term-effects-long-term-impact-report-federal-trade-commission; Carrier MA. Citizen petitions: long, late-filed, and at-last denied. Am Univ Law Rev. 2017;66(2): Article 1. Available from: http://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol66/iss2/1; Carrier MA, Wander D. Citizen petitions: an empirical study. Cardozo Law Rev. 2012;34:249-93. Available from: http://cardozolawreview.com/content/34-1/Carrier.34.1.pdf; Gottlieb S. Antitrust concerns and the FDA approval process (statement before the U.S. House Committee on the Judiciary, Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law). Washington (DC): U.S. House of Representatives; 2017 Jul 27. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm568869.htm; Carrier MA, Shadowen SD. Product hopping: a new framework. Notre Dame Law Rev. 2016 Nov;92(1): Article 4. Available from: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4680&context=ndlr; Kesselheim AS. Intellectual property policy in the pharmaceutical sciences: the effect of inappropriate patents and market exclusivity extensions on the health care system. AAPS J. 2007;9(3):E306-11. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17915832; Thomas K. 2 former drug executives charged with price fixing. The New York Times [Internet]. 2016 Dec 14 [cited 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://nyti.ms/2jR2Iqv; Thomas K. 20 states accuse generic drug companies of price fixing. The New York Times [Internet]. 2016 Dec 15 [cited 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://nyti.ms/2k6j5iH

Emerging Biosimilars Market Should Be Monitored

The rising cost of cancer drugs over the past several years has been driven largely by high-priced biological products, or “biologics,” which are products isolated from living organisms or systems.21 Patents for some cancer biologics have expired and many more will expire over the next few years, raising hopes that biosimilars—like generic drugs—will provide financial relief. Biosimilars are products that are highly similar to and have no clinically meaningful differences from an existing FDA-approved product. However, biologic products, including biosimilars, are far more difficult and expensive to develop and manufacture than other drugs, making it difficult to predict cost savings. Lower costs and increased patient access to biologics have occurred in Europe, where nearly 30 biosimilars have been approved since 2006.22 The U.S. biosimilars market has emerged more slowly. An abbreviated pathway for biosimilar approval was created by the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act of 2009, and FDA has issued several guidance documents for industry to support the development of biosimilars.23 The first two biosimilars for the treatment of cancer—one for bevacizumab (Avastin) and one for trastuzumab (Herceptin)—were recently approved,24,25 and others are under development.26 FDA should continue to monitor the emerging U.S. biosimilars landscape and ensure that approval processes and manufacturing oversight are functioning efficiently such that biosimilar products can be made available to the American public. Whenever appropriate, lessons on biosimilar regulation should be gleaned from the European Medicines Agency.

References

- Association for Accessible Medicines. Generic drug access and savings in the U.S. Washington (DC): AAM; 2017 Jun 12. Available from: https://www.accessiblemeds.org/resources/blog/2017-generic-drug-access-and-savings-us-report

- Berndt ER, Aitken ML. Brand loyalty, generic entry and price competition in pharmaceuticals in the quarter century after the 1984 Waxman-Hatch legislation. Int J Econ Bus. 2011 Aug 4;18(2):177-201. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/figure/10.1080/13571516.2011.584423

- Express Scripts Lab. Express Scripts 2015 drug trend report executive summary. St. Louis (MO): The Express Scripts Lab; 2016 Mar. Available from: https://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/~/media/e6bfbe7c0ed34c6aa20ff451a6e18d0d.ashx

- QuintilesIMS Institute. Medicines use and spending in the U.S.: a review of 2016 and outlook to 2021. Parsippany (NJ): QuintilesIMS Institute; 2017 May. Available from: http://www.imshealth.com/en/thought-leadership/quintilesims-institute/reports/medicines-use-and-spending-in-the-us-review-of-2016-outlook-to-2021

- Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS, Polinski JM, Hutchins D, Matlin OS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):400-7. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25222387

- Langreth R, Migliozzi B, Gokhale K. The U.S. pays a lot more for top drugs than other countries. Bloomberg [Internet]. 2015 Dec 18 [cited 2017 Sep 28]. Available from: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-drug-prices

- Wouters OJ, Kanavos PG, McKee M. Comparing generic drug markets in Europe and the United States: prices, volumes, and spending. Milbank Q. 2017;95(3):554-601. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28895227

- Gooi M, Bell CM. Differences in generic drug prices between the U.S. and Canada. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2008;6(1):19-26. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18774867

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Generic competition and drug prices [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; [updated 2015 May 13; cited 2017 Aug 30]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/ucm129385.htm

- Dave CV, Kesselheim AS, Fox ER, Qiu P, Hartzema A. High generic drug prices and market competition: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167(3):145-51. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28672324

- Becker DJ, Talwar S, Levy BP, Thorn M, Roitman J, Blum RH, et al. Impact of oncology drug shortages on patient therapy: unplanned treatment changes. J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(4):e122-8. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23942928

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Generic drugs under Medicare: Part D generic drug prices declined overall, but some had extraordinary price increases. Washington (DC): GAO; 2016 Aug. Available from: http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/679022.pdf

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. ASPE Issue Brief: Understanding recent trends in generic drug prices. Washington (DC): ASPE; 2016 Jan 27. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/175071/GenericsDrugpaperr.pdf

- Woodcock J. Generic Drug User Fee Act Reauthorization (GDUFA II), Biosimilar User Fee Act Reauthorization (BsUFA II) [Testimony before U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce Subcommittee on Health] [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): U.S. Food and Drug Administration; 2017 March 2 [cited 2017 Aug 18]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Testimony/ucm548273.htm

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA tackles drug competition to improve patient access [News Release]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2017 Jun 27. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/UCM564725.htm

- Gottlieb S. Reducing the hurdles for complex generic drug development. FDA Voice [Internet]. 2017 Oct 2 [cited 2017 Dec 17]. Available from: https://blogs.fda.gov/fdavoice/index.php/2017/10/reducing-the-hurdles-for-complex-generic-drug-development

- Cole AL, Sanoff HK, Dusetzina SB. Possible insufficiency of generic price competition to contain prices for orally administered anticancer therapies. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(11):1679-80. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28892541

- Gupta R, Kesselheim AS, Downing N, Greene J, Ross JS. Generic drug approvals since the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(9):1391-3. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27428055

- Gagnon MA, Volesky KD. Merger mania: mergers and acquisitions in the generic drug sector from 1995 to 2016. Global Health. 2017;13(1):62. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28830481

- Haninger K, Jessup A, Koehler K. ASPE Issue Brief: Economic analysis of the causes of drug shortages. Washington (DC): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 2011 Oct. Available from: https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/108986/ib.pdf

- Fitch K, Pelizzari PM, Pyenson B. Cost drivers of cancer care: a retrospective analysis of Medicare and commercially insured population claim data 2004-2014. Milliman (commissioned by the Community Oncology Alliance); 2016 Apr. Available from: http://www.milliman.com/insight/2016/Cost-drivers-of-cancer-care-A-retrospective-analysis-of-Medicare-and-commercially-insured-population-claim-data-2004-2014

- QuintilesIMS. The impact of biosimilar competition in Europe. London (UK): QuintilesIMS; 2017 May. Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/DocsRoom/documents/23102

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Biosimilars [Internet]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; [updated 2017 Sep 21; cited 2017 Dec 15]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm290967.htm

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of certain breast and stomach cancers [News Release]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2017 Dec 1. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm587378.htm

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first biosimilar for the treatment of cancer [News Release]. Silver Spring (MD): FDA; 2017 Sep 14. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm576112.htm

- Nabhan C, Parsad S, Mato AR, Feinberg BA. Biosimilars in oncology in the United States: a review. JAMA Oncol. [Epub 2017 Jul 20]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28727871